Aero Evolution: Kona Pro Bike Positions

To start, from an aerodynamic perspective, athletes are dialed! Bike positions, equipment, and bottle set-ups are no longer an afterthought. If you’re not paying attention to these elements, you’re putting yourself at a material disadvantage on the race course.

Before I dive into this piece, I want to acknowledge a few things:

- These are static images taken at a single moment in time during a 180k race segment.

- Camera angles can distort positions, and athletes may not be at the same point in the pedal stroke, so these comparisons are made at a high level.

I’m also going to assume that athletes have arrived at their positions through a deliberate process, supported by trial and error, bike fit professionals, and some form of aerodynamic testing—whether in the wind tunnel, velodrome, or using modern field-testing devices.

Observations and Trends

Steep vs Slack’ish

Most athletes are riding steep, with saddles pushed forward or their bodies positioned so they sit forward relative to the bottom bracket. In my fit studio, I use a motion capture system to obtain a measurement similar to KOPS (knee over pedal spindle) to gauge how steeply an athlete is riding. While there is no definitive number, I use a range or established norms to ensure an athlete is in the ballpark. This measurement serves as a key variable I can adjust to optimize their fit.

For this article, another way to assess steepness is by comparing hip position relative to the bottom bracket. In the image above, you can see that Lionel Sanders is positioned further back on the bike compared to Patrick Lange.

A few other riders, like Matthew Marquardt and Cameron Wurf, adopt “slacker” positions. Cameron, racing in the pro tour, adheres to UCI regulations requiring the saddle to be at least 50mm behind the bottom bracket. I’m not sure whether he adjusts his position for triathlon or maintains the same setup, but he does a solid job of rotating his pelvis forward to maintain an open hip angle, mitigating any potential impact on biomechanics.

Hip Angle

When athletes report power loss due to bike position, I typically start by evaluating their hip angle. A closed hip angle can create restriction over the top of the pedal stroke. This closure can result from several factors: bars set too low, excessive reach, a saddle positioned too far back, or a poorly suited saddle that limits anterior pelvic tilt.

For some athletes, a closed hip angle doesn’t pose a significant problem- I can give you numerous examples of triathletes and pro cyclists who have performed exceptionally well with closed hip angles. For others, a closed hip angle can be the root of the power loss issue.

The image above illustrates the contrast between hip angles of Lionel Sanders and Magnus Ditlev. Although their pedal positions aren’t identical, it’s evident that Lionel rides with a more closed hip angle.

Matthew Marquardt is another athlete to ride with more closed hip angles. While this may or may not affect cycling power, the key question is whether this impacts their performance during the marathon. If I were working with these athletes, this would be an area for further investigation.

Back Angle & Reach

Back angle and reach are interdependent. While back angles haven’t changed significantly over the years, athletes have shifted away from the “how low can you go” mindset. Instead, the bars have gone up and out, with athletes raising their front ends an estimated ~40-60mm and extending their reach ~60-100mm compared to positions of the past.

Athletes are also adding 10-20 degrees of bar tilt, which helps support the upper body, relax the shoulders, and create a “pocket” for the athlete to hide their head behind their hands. This configuration results in what I call a solid, “all-day” aero position, allowing athletes to settle comfortably and keep their heads low without reaching for their bar drop.

To illustrate the change in positioning, I’ll use Sam Appleton as an example since I have his fit coordinates from the past several years. Sam’s position looks great in either setup, but you can see how much modern positions have evolved.

| Old Position | New Position |

| Stack: 600mm | Stack: 650mm (+50mm) |

| Reach: 450mm | Reach: 530mm (+80mm) |

These are significant changes. If this trend continues—and I believe it will—bike manufacturers will need to account for the extra length and height in future designs.

I understand this is a challenging task, as creating a bike that fits everyone isn’t easy. Manufacturers have done an excellent job expanding the fit window of their bikes over the years. However, could we see a return to the days when bikes or brands offered distinct fit characteristics—like long and low, short and shallow, or now, long and tall?

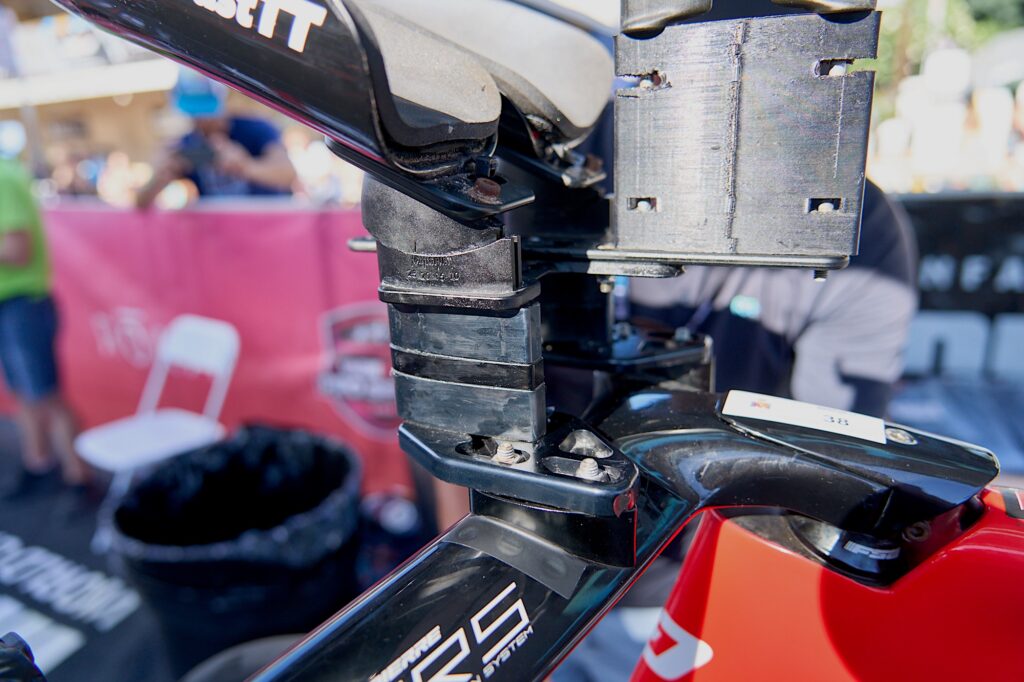

With athletes positioned so far over the front end, we need to find ways to incorporate more frame into the design rather than relying on spacers, bolts, and extenders to achieve these new positions. Currently, it’s concerning to see athletes resorting to DIY or third-party solutions to extend and raise their front ends, placing significant trust in these “Lego-like” constructs to support the weight of their upper bodies.

Outliers

Kristian Blummenfelt and Gustav Iden have the most unorthodox positions. Gustav has maintained a more consistent position over the years, whereas Kristian’s approach has been more variable. Their setups have shifted from highly aero-driven to comfort-focused and back again.

Not a fan of KB’s position here. I have no doubt that the position tests fast and helps narrow and elongate his frontal aero profile. However, I think this can be done with a position that might be more comfortable and robust.

When Gustav is on the nose of the saddle throwing down power, this position is not quite as “superman” as was expected. Still, I think bringing the front end back ~20-30mm and lowering it ~20mm would be a more orthodox position by today’s standards.

While these positions may test well aerodynamically, a truly effective position must be holistic. I’ll elaborate on the fitting pillars I use when working with athletes in future articles, but I’ll leave you with this:

The primary goal of the time trial position is to reduce aerodynamic drag in the quest for speed, but the fastest positions are rarely purely aero-driven.

Quick Takes on Individual Rider Positions

For this section, I’m going to give you my quick high-level thoughts on the bike positions of the athletes below. I’d love to get your thoughts as well in the comments section.

Sam Laidlow has a great holistic looking bike position. He does seem to put a bit more weight on the front end compared to someone like Magnus, but this is a great “all day” aero position that is achievable by most triathletes.

I really like Magnus Ditlev’s position—it checks all the boxes and looks incredibly comfortable. I don’t see anything I would change, especially knowing the thought and effort that went into the position you see above.

Robert Kallin could be Magnus’s twin on a bike and that’s not a bad thing.

Patrick Lange rides in a steep, compact position. Riders often fall into one of two categories: bar chasers or saddle chasers. A bar chaser, like Patrick, tends to preserve their shoulder angle and may pull themselves off the front of the saddle if the bars are extended too far. In contrast, saddle chasers stay firmly seated and extend their arm and shoulder angles as the bars are pushed forward—think “superman” position.

Leon Chevalier is another athlete with a textbook position. He rides forward with a relaxed upper body and his helmet mates nicely to his back.

I’ve worked with Rudy Von Berg for a number of years and I think his position has progressed nicely. He rides a position that is both long and low while maintaining a relaxed posture and a great head position.

I’ve used Lionel Sanders as an example of a rider sitting further back on the bike with a more closed-off hip angle compared to his competitors. This might be the most aerodynamic I’ve ever seen him, but his upper and lower body appear incongruent. I’d be curious to see the impact of moving him forward 40-50mm to open his hip angle, and slightly adjusting the bars forward to maintain reach. The goal would be to retain the aerodynamic profile of his current position while improving biomechanics for better power production. But, who knows—maybe he can crush it in the position above?

Daniel Baekkegard doesn’t ride quite as long as others, but I don’t have much to critique here. Based on this image, maybe he could work on rolling his pelvis more forward?

Ben Kanute’s arrival at his position was well documented in a recent Slowtwitch article where he visited the Zipp wind tunnel. Ben’s position looks great and I’m glad he decided that going lower in the front end was not going to improve his aerodynamics.

Braden Currie rides in a more traditional, textbook throwback position. He seems to have some room to stretch out if needed, but currently rides with a more vertical upper arm and a larger drop. The newer, higher, and longer positions might offer more comfort and could be worth considering here.

I think the camera angle is distorting Mathias Petersen‘s position. I’ve seen other images of his position and they look much better than what we are seeing above.

Bradley Weiss had a great ride in Kona. My quick take: he looks a bit too comfortable and might benefit from lowering and extending the front end more.

Mike Phillips has a really nice position. If Mike asked for my advice, I’d look to bring his front end up and see if it has any impact on drag. As long as he could keep his head low, I think there would be minimal impact on aerodynamics and he could potentially be more relaxed on the front end.

If I were working with Arnaud Guilloux, I’d add more tilt to the bars. After doing so, I’d probably want to raise his front end 10-20mm.

Matt Hanson has a good position. Something I might try, would be to add more upward angulation to his bars and then raise the front end around 10mm.

Igor Amorelli is riding really steep and basically coming off the front of his arm cups. Looks like he might be doing something with his hands here…like opening nutrition?

Not the best angle of Tristan Olij, but from sitting here at my computer, this position passes the eyeball test.

Reinaldo Colucci is one of the few athletes riding with flat arms—a setup that worked well for Jan Frodeno. As long as he feels locked in on the front end, his position looks solid, and his head position is on point.

Gregory Barnaby rides a long and low position that flattens out his back and does a great job of keeping his head low.

Trevor Foley was having a great ride until an unfortunate crash near the end of the bike leg ruined his day. His position is textbook—he rides steep, maintaining a relaxed posture over the front end, which allows him to keep his head low. In terms of reach, he doesn’t stretch out as much as some athletes, but he doesn’t ride compact either; he sits comfortably in the middle.

The evolution of bike positions and technology at Kona reflects the relentless pursuit of speed by reducing resistive forces—wind, road, and drivetrain. While trends point toward steeper angles, higher front ends, and extended reaches, the goal remains the same: maximizing speed while balancing personalized comfort, biomechanical efficiency, and power output.

It’s exciting to consider where we go from here. From a bike fit perspective, these modern positions appear to not only be faster, but also significantly more comfortable.

-Mat

Tags:

Bike FitCyclingKonaContinue the discussion at forum.slowtwitch.com

25 more replies

Great article and interesting to see the various positions. I definitely feel a loss of power moving into my aero position. I’m sure some of that can be explained by my relatively recent intro tot he sport. Coming from an MTB heavy background I’m sure my power sweet spot has been naturally with a more upright position.

To me I would struggle mightily in a couple of those fits.

As you look at the more extreme example of this, the riders have gone from “riding a bicycle” to “running on a bicycle”, which I’m sure helps Triathletes.

No way is this the fastest wat to ride a bike (if you don’t have to run after dismounting). World class Time Trialist’s and Hour Record holders do not sit like this, regardless of the UCI’s stupid rules.

Wait, don’t they ride the way they do specially because of the UCI rules? Saddle setback and maximum reach seems to outlaw most of these positions for UCI events

You are correct.

I find it funny that was is old is new again. these positions are not new, they are mostly the ones we rode in the very early days with retro fitted road bikes and later 80 degree seat tube tri bikes. The one piece to this puzzle we did not understand was the shorter cranks to open up the him angle. I thing Marqardt is still a victim of this(think I saw he was still riding 175’s) and no doubt a few others could go shorter too.

I was watching an old video of me in 1990 and I was in the exact position that Iden is using now. Of course it did not feel that great for longer distances, so I along with most others morphed into what you see Lange riding today. 90 degree elbows, on the nose and as far forward as was allowed was the standard tri fit for the early years…

Forgot to add that those long lay down bars make all the difference too in comfort, while we had one tiny pad that was usually too hard. I actually put two of them together to make for a longer surface area, worked really well. Took awhile, but they are popping out of the printers like hotcakes now I bet!

One of the big things about Tadej Pogacar’s position is the fact he is coming much more forward than traditional road positions, and if you watch WT TT’s almost all riders are at the tip of their saddles.

Looking at an article about Remco’s TT bike - saddle as far forward as it can go per regs.

It would be interesting to see where TT positions in the world tour would go with regards to loosened regulations, but most of the evidence is that they would stretch out and go forward, much like the triathletes are doing.

I agree with all - I should have been more specific. The stretched out, longer position is certainly more optimal. In England, where TT’ing is a fine art, and the actual “birth” of the Superman position, they race like this utilizing a relaxed version of the UCI’s rules. My issue is the higher “more comfortable” position, which IMHO only works because of fairings disguised as aerobars, fairings disguised as hydration, and fairings disguised as storage.

The problem is that we are really talking about the fastest position for two completely different sports. Any WT cyclists who have come to tri have relaxed their positions on the TT bike because - it’s not a TT race. Knibb changes her position for TT as well. I just think that the evolution for the TT bikes is significantly faster bike AND run. I would be interested to see how the WT guys would be set up if they did a 112 mile TT as a stage of the tour. I would suspect significant changes would be in everyone’s position, even not running off it. Because while “more comfortable” doesn’t sound as sexy as “more aero”, holding the position for 112 obviously is significantly faster. Therefore…it might be exactly the fastest way to ride these long distances.

Can you link the YT video? If it is on YT of course…

Jeroen

i don’t know about the video, but i can attest that monty rode further forward and with less of a drop than most riders. the only thing he didn’t do was ride with an upward arm tilt, but the bars back then were not fairings as many are today. riding with an upward tilt likely wouldn’t have been a benefit.

WC pro cyclists ride with more closed hip angles because it’s more aero (having the thighs fill all the space under their torsos) vs open hip angles where there is a lot more space between the torso and the thighs and the top of the stroke. At least that is my understanding. Also, they generally are significantly more flexible than their WC triathlon counterparts - probably in large part due to having a whole team of people to massage and stretch out their bodies on a daily basis - which allows them to pull off a more closed position without loss of power or biomechanical issue.

Also they don’t need to hold that position as long as an IM triathlete does and they don’t have to run afterward of course. But the notion that we would see a lot of open hip angles among the WC TT cyclists if the ICU relaxed their rules doesn’t hold water for me. This is just one of the reasons, maybe/probably not even the most important reason.

then why are we seeing those riders moving to shorter cranks, like triathletes have been doing for 20 years now??? Other than hip angle and more aerodynamic, what would be the reason?

I have no doubt at Mounty’s response, I just love to watch those old tri videos when I’m on the trainer.

Recently I saw a few with a peep young lance armstrong already being blatantly bold on the bike shouting to mark allen and mike pigg to do some work at the front too

It took me 20 years to get those old VHS tapes onto a DVD, how the hell do I get that to YouTube?? Nothing I have anymore runs a dvd even, maybe have to go to a place to get it on your hard drive???

And I have a lot of these old tapes too.

Shorter cranks allow people to get their torsos lower and backs flatter. WC TT cyclists can take advantage of this because they have the flexibility to get lower if just their thighs have the space at the top of the stroke. As someone who has long lower legs I can personally attest that shorter cranks have allowed me to do this very thing. My thighs still brush my rib cage but my torso is lower/back is flatter vs me on longer cranks.